Arguably, the most troublesome and complicated problem that may occur with the optical system of the eye is farsightedness. Also known as hyperopia, it is most often confused with presbyopia, which is brought on by the aging of the eye that eventually requires us to wear reading glasses or bifocals.

Both conditions result in difficulty focusing near objects, and both require power to be added (plus power lenses) to our optical system. But while presbyopia is caused by the lens’s gradual loss of flexibility and focusing ability over time (aging), hyperopia is the result a shortage of natural focusing power to begin with, that is then made worse by the same natural aging process.

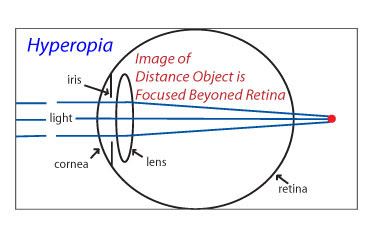

In other words, farsightedness occurs when the naturally available focusing power in the eye is less than what is necessary for the size of the eye. Thus, the focal point of the eye falls behind the retina. Some describe this as an eye that is simply too small.

Both conditions, hyperopia and presbyopia, can cause blurry vision at near, but for different reasons. While presbyopia directly affects only near vision, farsightedness will eventually cause blurry vision at distance as well as near.

Most Farsighted people find this surprising. Many will say that they had perfect vision when they were young, but as they aged they started having problems at near and then finally at distance, as well. The exact scenario simply depends on the individuals prescription. For some, their hyperopia is so great that they have to wear glasses very early in life. Many of them will also encounter problems with so called “lazy eye” and amblyopia. These more farsighted individuals actually have an easier time understanding their prescriptions. They have a whole life time of experience. Others, with much less hyperopia, compensate for the problem until they can do so no more. It is not uncommon for farsighted patients to sometimes wear their glasses and at other times, do without them. Their needs are demand driven.

So, how did these farsighted folks see clearly at distance when they were younger if they actually had too little focusing power built into the eye to begin with? Well, they “borrowed” it from the near focusing system. In other words, farsighted eyes use the flexible lens meant only to actively focus at near, to focus at distance as well.

Confused yet? Well, of all the conditions of the eye hyperopia is by far the most difficult to understand, explain, and deal with. Unfortunately, a quick internet search will get you a similarly quick (and short) answer – the best description I’ve run across, however, was written by Derral Eves at SouthWest Vision – To understand it, you have to understand how the normal eye works.

In the normal (emmetropia) eye, viewing objects at distance requires absolutely no focusing or adjusting of the lens – “distance” actually means a certain size beyond 20ft, but let’s not get lost in the weeds.

Basically, the normal eye is pre-set and already focused for distance objects. Without adjusting in any way shape or form, it will naturally focus light onto the retina just by pointing in the right direction – as long as the object is beyond a certain size and distance.

Think of the old disposable cameras we used to buy. They were also pre-set for a certain distance. There was no manual or autofocus involved. But if you tried to take a picture up close, it would just be blurry. You couldn’t adjust the image.

Luckily, the human eye is much better than a disposable camera. It’s actually more like 3D video camera, and it has a very good autofocus mechanism. Unlike the disposable camera that cannot focus at near, the eye can. As noted above, distance objects are naturally focused on the retina without any additional adjustment than what is already built into the eye. When a distance object is brought closer, however, the image would focus beyond the retina – unless the eye could somehow adjust to keep it on the retina.

When images focus beyond the retina, the muscles around the lens automatically adjust, causing the lens to change shape (and power). This re-focuses the light onto the retina. This is called accommodation.

This whole process is automatic and involuntary. We look at a distance, and our eyes relax. We look at something up close, and our eyes focus. This is how the eyes work, and how we see at all distances. As we age, the lens gets less flexible and it makes auto focusing more difficult – we’re not exactly sure why. But for whatever reason, lens thickening, stretching of the fibers connected to the lens, etc., we lose our ability to flex it and add power to our own system.

As a result, we move farther away from things that are too close as we get older. Think of young children sitting very close to the television. They do so because they can. As we age, we move away from the TV. We move away from the front rows of the movie theater. And ultimately, by the time reach about the age of 40 or so, we move away from books and other near objects. At this point, this loss of flexibility becomes a problem and we give it a name: Presbyopia. To correct this problem, we use reading glasses and bifocals.

Hyperopia seems very similar to presbyopia. As noted, both result in problems with reading at some point. And both problems can be helped via the use of reading glasses. But hyperopia is not a situation of a normal eye affected by the normal aging process. Hyperopia is a condition of an under powered optical system that the aging process eventually reveals and exacerbates.

When the hyperopic eye views a distant object, the light is focused beyond the retina. Again, this is because the eye is to small for the optical power available — it’s too weak powered. Just as in the normal eye viewing a near object, however, whenever light falls behind the retina, however, the eye’s autofocus (accommodation) system kicks into action and brings the light into focus on the retina. In this way, the farsighted eye “borrows” from the near focusing system to adjust for distance. Now when the same farsighted eye views some object up close, it doesn’t have enough focusing power left over. This results in a blurry image of the near object, even though the eye is not presbyopic! Thus, the confusion.

So, Farsightedness means that the eyes have to focus (accommodate) not just at near, like normal, but everywhere and at all times. As a result, the focusing system can be unstable. If you’re rested, you’ll see fine. If you’re tired, you may experience blur, most commonly at night.

The symptoms associated with hyperopia can be demand driven. The more near work you do, the more symptoms you will have and the more plus power you will need. Read a lot of fine print or do heavy computer work and you will wish your glasses were stronger. Often, farsighted prescriptions are described as “reading” prescriptions, to be worn mostly at near or computer. That’s because the power is too much to be tolerated at distance, but necessary at near to prevent eyestrain and/or headaches.

All this focusing can cause an array of symptoms: headaches, blurry vision at distance after reading, poor night vision. It can even lead to accommodative spasm and what really is farsightedness will appear to be Nearsightedness (pseudomyopia).

The best farsighted prescriptions are a fine balance between how much work the eyes are able to do (accommodation), and how much power is ultimately added to the system via your prescription lenses. In other words, it’s not just the prescription that matters. It’s how much your eyes can compensate, plus the prescription. As time passes, you can compensate less. Therefore, your prescription increases.

Moreover, going from one visual demand extreme to the other – jet pilot to software engineer – would require quite the change in prescription, simply based on visual demand. In other words, besides the natural aging process, visual demands can also necessitate that a farsighted prescription be increased.

Finally, since farsighted eyes are constantly adjusting for different visual demands, going too long between prescription changes can be a real problem. The eyes get used to working a certain amount, and they will gradually adjust to whatever natural changes occur – even if it is a great deal of change. The eyes and the brain work together to compensate and adjust for the imperfections. If too much of a prescription change is made, no matter how much clearer it makes things, it may be difficult to tolerate. The visual system will actually continue to adjust for the previous imperfections until it realizes they are no longer there. For this reason, it’s best to update your prescription at minimum every two years. Without a doubt, small changes over time are always easier to adapt to.